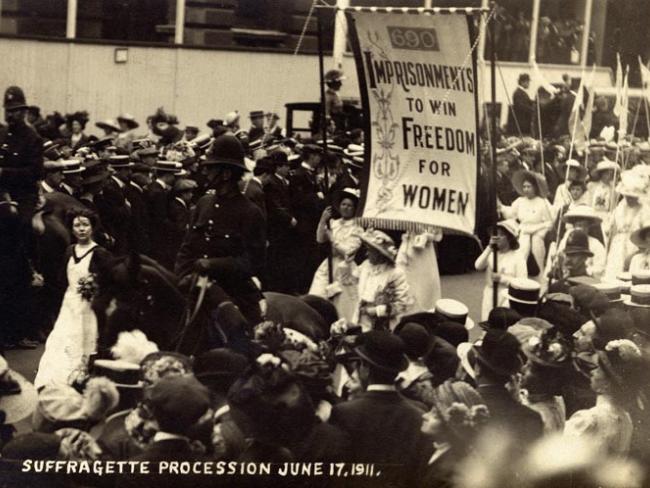

The 1911 census was widely boycotted by suffragettes, organising under the slogan, “No Vote, No Census”. Photo LSE Library.

To run a nation you need to know about who lives within. Otherwise you can’t govern the economy or health, and much else besides…

Censuses provide detailed information about national demographics and also play an important part in deciding on resource allocation to service providers. They can bring people together and give us a true sense of the society we live in. But they can also divide.

The development of a regular counting of the population of Britain was prompted by John Rickman, a government official, who devised the methods for the first British census in 1801, and who prepared census reports up to 1831.

The main aim of the March 1801 census was to assess how many men were fit to fight in the war against France. It was a rough headcount and stated that the population of England, Scotland and Wales was 10.9 million.

The nineteenth century censuses registered the great shifts of population from the country to the towns and cities as new industries sprang up. For example, Manchester grew from 70,409 people in the 1801 census to 543,872 in 1901. Adjoining places like Salford grew at a similar rate.

The first four censuses up to 1831 were mainly headcounts with little personal information collected. Then things began to change.

The 1841 census recorded the names of residents, and the ages of those over 15, as well as occupations. Also it noted whether or not the occupants resided in the same county in which they were born, or whether they had been born in “foreign parts” of Britain.

The 1851 census was the first to record the full details of birth location for individuals. It also required the exact age of each member of the household and recorded each person’s relationship to the head of the household, as well as any members out working at night, and anyone with a disability.

William Farr, Superintendent of Statistics, was responsible for producing the censuses of 1851, 1861 and 1871. Coming from a medical background, he was interested in using data from the Births, Marriages and Deaths Register to chart the incidences of epidemic diseases.

This had a huge impact. For instance, Farr’s work on smallpox led to legislation in 1853 making vaccination compulsory.

From 1851 on, the census asked for more detail about people’s occupations, identifying over 300 categories in total. Agricultural work had declined, while manufacturing jobs, mining and professional services had increased. “Masters” in trade and manufacture were required to state the number of employees they had working under them.

The nineteenth century saw a huge expansion in the information collected. By 1851 information on rank, occupation, profession was gathered, for example. Questions about infirmity were added in 1851, then dropped in 1921.

Enter religion

By the end of the twentieth century the census was recording details about where people were born, indoor sanitation and so on. Then, in 2001, religion found its way into the census.

The question about religion was voluntary, but symptomatic of a desire by governments to slice up and fragment the people of Britain. The census had expanded from clear social questions, such as dwellings with indoor sanitation, to add divisive questions about personal identity.

Already in 1991 the government had decided asking people the straight question of where they were born was not enough. The census asked for information about “ethnicity”, a vague and potentially misleading concept.

‘The census expanded from clear social questions to add divisive ones about personal identity…’

The religion question did not go unopposed. The British Humanist Association in particular criticised the phrasing, “What is your religion”, as a leading question that would exaggerate those actually practising a religion.

In the 2011 census immigrants were asked about the date of their arrival and how long they intended to stay. Those whose first language was not English were required to say how well they spoke the language.

All well and good – but what about those living and working illegally, who of course did not fill in the forms?

No wonder official figures in the census for migration seem woefully inaccurate compared with the estimated total British population. The lack of proper border controls means Britain cannot plan properly, leaving the country vulnerable in a crisis like a recession or a pandemic.

In any case, previous experience had suggested that immigrants, whether legal or not, might not respond well to questions that could affect their livelihood. The 1991 census was seen by many as designed to identify people who would have to pay the poll tax – which many didn’t want to do.

The result was that the population of Britain was undercounted by over a million, and the undercounting of immigrants was particularly marked. Later adjustments in the light of new evidence had to raise the number of immigrants by a whopping 23 per cent.

Most recently, in 2021, people were asked about their sexual orientation. Another attempt to create division. But the question was full of terms whose meaning was not familiar to many, such as “gender”, “trans man” and so on.

The result was a farce: Newham, for example, appeared to have the highest number of trans people. Brighton ranked 20th among UK boroughs. Overall, 0.4 per cent of people with English as a first language declared themselves as trans, against 2.2 per cent of those who did not speak English well.

In 2020 the UK’s national statistician, Ian Diamond, floated the idea that the 2021 census might be the last. But so many people criticised this proposal that it now seems likely that the pattern of censuses will continue. In June the UK Statistics Authority recommended a census in 2031. A good outcome.

Obviously there is no guarantee that having accurate data means it will be used well, but without it there is little chance of making the right decisions.

• Correction. The print edition of Workers November/December 2025 incorrectly says that legislation making smallpox vaccination compulsory was introduced in 1835. The correct date is 1853, as this article states.